Used under a Creative Commons Licence

The Fine Line Between Copyright Infringement and Artistic Creativity

This is an updated version of an old post, click here to see the original.

If you hang around creative people long enough, you may just hear the same confession again and again, usually in a half‑whisper: “I borrowed this from…”

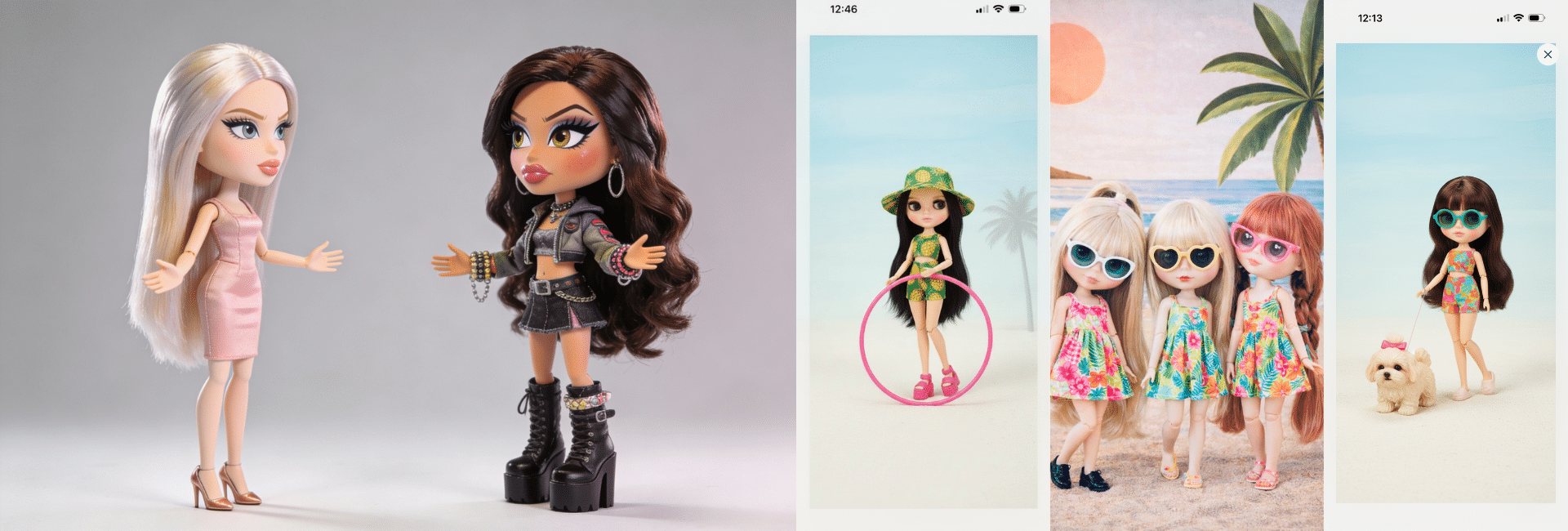

A movie poster pose, a doll, a product shot, a classic photograph – all quietly smuggled into new work in the name of irony, tribute or social commentary.

Most of the time, nobody sues. That silence can feel like permission.

But as we find out in our law firm from time to time with our creative clients – it isn’t.

Copyright law cares far less about your motives than about what, exactly, you took and how closely your work tracks the original.

You can set out to critique consumer culture or celebrate a cultural icon and still cross the line into infringement.

This article looks at how far you can go in Australia before “inspiration” becomes copying, using some famous overseas disputes as examples. Join us for the journey.

When Barbie becomes art: the Food Chain Barbie case

US photographer Tom Forsythe’s “Food Chain Barbie” series is a classic example of art based on someone else’s product. The series, consisting of 78 photographs, shows nude Barbie dolls in absurd, sometimes sexualised positions, often juxtaposed with kitchen appliances – Barbie in a malt machine, Barbie heads in a fondue pot, Barbie dolls wrapped in tortillas and baked in a casserole dish.

Mattel, which owns copyright and trade marks in Barbie, sued Forsythe for copyright infringement, trade mark infringement and misleading conduct. The court accepted that Mattel owns copyright in Barbie’s unadorned head and figure and that photographing the doll and reproducing those photos made out a prima facie case of infringement in the US.

The outcome turned on the US “fair use” defence. Forsythe argued his work was a parody and social commentary on the objectification of women and the “beauty myth” symbolised by Barbie. The court agreed that:

- His photos transformed Barbie’s glamorous image into something absurd and critical.

- The lighting, composition and context created a new meaning and message.

- The images did not harm Mattel’s market for Barbie dolls or licensed derivative products.

On appeal, the judges held that the public benefit in allowing artistic freedom and criticism of a cultural icon outweighed Mattel’s interests. Forsythe’s use was “fair use”, so no copyright infringement was found.

- Australian angle: Australia does not have a broad “fair use” exception. Instead, there are narrower defences for things like genuine criticism or review of a work. Any Australian court would ask whether the criticism is of the work or subject itself (here, Barbie) and whether the new work reproduces a “substantial part” of the original. There is no guarantee that Food Chain Barbie would be protected here.

- Altered dolls and “Dungeon Dolls”: how far can you change a product?

- In another US case, artist Susan Pitt created “Dungeon Dolls” – altered Barbie dolls dressed in sadomasochistic outfits and photographed for sale and display online. Mattel again sued for copyright infringement of its “Superstar Barbie”.

The court accepted that Pitt used the entire copyrighted head, but noted that she had substantially changed the decoration of the head and body. Although the dolls still evoked Barbie, the court found the transformations sufficient that they did not amount to infringement in that context.

Takeaway: Even when you start with someone else’s product, significant transformation in appearance and message can reduce infringement risk. But this is always a question of degree and context.

Parodying a famous photograph: the Demi Moore / Naked Gun ad

Sometimes a photograph – not a product – is the cultural icon. A famous example is Annie Leibovitz’s 1991 Vanity Fair portrait of a nude, heavily pregnant Demi Moore.

Paramount Pictures later promoted the film “Naked Gun 33⅓: The Final Insult” with a spoof ad: a pregnant model posed like Demi Moore, but with actor Leslie Nielsen’s face superimposed. Leibovitz sued for copyright infringement.

The US court held that:

- The ad closely mimicked the pose, lighting and backdrop of the original.

- However, the photographer had taken “no more than necessary” to call to mind the Demi Moore photo.

- The use was a parody and qualified as fair use, so there was no infringement.

Australian angle: In Australia, the core test is whether there has been a substantial reproduction of the photograph. Copyright protects the expression, not the idea. Taking a pregnancy portrait in a similar pose is not necessarily infringing, but closely copying the specific lighting, composition, look and styling may be. There is no broad parody defence; each case turns on how much has been taken and for what purpose.

Moral rights: when your work is distorted or unattributed

Australian photographers also have moral rights, introduced in 2002. These are personal rights that remain with the photographer even if copyright is assigned:

The right of attribution – to be named as the author and not have someone else falsely credited.

The right of integrity – not to have your work subjected to derogatory treatment that prejudices your honour or reputation.

Examples of potential moral rights issues include:

- Colourising a well‑known black‑and‑white photograph against the photographer’s wishes.

- Publishing a photograph in a book or online without crediting the photographer.

- Heavily distorting a recognisable image (for example, the Demi Moore portrait) in a way that could harm the photographer’s reputation.

Even where copyright infringement is arguable, a misuse of the work may still breach the photographer’s moral rights.

Copying in a different medium: photos to sculptures

Copyright issues are not limited to straight photo‑to‑photo copying. In one well‑known US case, photographer Art Rogers licensed his image “String of Puppies” to a greeting card company. Artist Jeff Koons then created a series of sculptures based closely on the photograph, selling them for substantial sums.

The court found that the sculptures substantially reproduced the original photograph and that copying in a different medium did not avoid infringement.

Relevant factors in these kinds of cases include:

- How closely the new work follows the original composition and detail.

- Whether the use is commercial or non‑commercial.

- How much of the original’s expressive content is taken.

- Whether the new work harms the copyright owner’s commercial interests.

Again, the same issues would be considered in Australia, but under our “substantial part” test rather than US fair use.

Myth‑busting: common copyright “creativity” myths

If you spend enough time around photographers and artists, you start to notice a certain folklore about copyright – a set of rules everyone “just knows” but that rarely survive contact with an actual judge. We repeat them like comforting mantras: “It’s parody, so it’s fine,” “I only changed it a bit,” “I’m not making money,” as if intention and vibe were what the law really cared about. They aren’t. Below are five of the most persistent myths that refuse to die – and the less romantic reality behind each of them.

“If it’s a parody, it’s always fine” – Not in Australia. We don’t have a broad, US‑style fair use defence. Limited exceptions for criticism or review are narrow.

“I changed it a bit, so it’s mine” – Small edits (cropping, filters, minor retouching) can still be a substantial reproduction if the key expressive elements are taken.

“New medium, new work” – Turning a photo into a sculpture, painting or mural can still infringe if it closely follows the original composition or detail.

“No money, no problem” – Lack of profit does not automatically save you; commerciality is just one factor.

“Crediting the photographer is enough” – Attribution does not excuse copying; and misuse can also breach the photographer’s moral rights.

The Australian position: case‑by‑case and fact‑specific

Australian courts have offered a practical rule of thumb: “what is worth copying is worth protecting”. But that is not the end of the story. Defences can apply, especially where:

The new work is genuinely for criticism or review of the original or its subject.

Only a small and non‑essential part of the copyright work is taken.

The overall impression is sufficiently different.

In photography and visual art, the overall visual impression is critical. Two works may look similar at a glance, but the legal question is whether the second takes a substantial part of the first’s protected expression. That is always a question of fact and degree.

If your photograph has been used out of context, distorted, stripped of attribution, or copied into another medium, you may have legal remedies. Conversely, if you want to use someone else’s product, image or artwork as part of your own work – even with the best intentions – it is sensible to get advice before you publish or sell it. Sometimes relatively small changes can significantly reduce your legal risk.

How we can assist you

- We regularly advise photographers, artists, designers and brands on copyright, moral rights and appropriation. We can help you:

- Assess whether a proposed project risks infringing another person’s photograph, artwork or product image.

- Enforce your rights if your work has been copied, distorted or used without permission.

- Draft licences and clearances for collaborative or commissioned projects.

- Develop internal guidelines for creative teams on when they must seek legal sign‑off.

In a field where small visual details matter, getting tailored advice early can save a great deal of cost and stress later.

Fun facts: when “healthy” claims go wrong

“100% extra virgin” oil that wasn’t – A “100% extra virgin olive oil” label led to undertakings after testing suggested it wasn’t extra virgin.

Fruit on the label, not in the bottle – Cottee’s banana & mango cordial showed real fruit but used flavouring only.

Apricot bars with mostly sultanas – Snack Right apricot slices featured apricots on pack, but had just 1.7% apricot and much more sultana and apple juice.

Flattened fruit that wasn’t just fruit – Roll‑Ups ads implied simple flattened fruit, but other ingredients and processes were involved.

Coke that “doesn’t make you fat” – Coca‑Cola’s myth‑busting ads had to be withdrawn and corrected after the ACCC stepped in.

How we can assist you

We work with food, beverage and FMCG businesses to develop truthful, compliant and effective health and environmental claims. We can help you:

- Review labels, packaging and advertising for compliance with the Australian Consumer Law.

- Design “lite”, “natural”, “organic”, “no added sugar” and similar claims that are properly substantiated.

- TAudit existing health and green claims against ACCC guidance and recent case law.

- Respond if the ACCC queries your marketing or if competitors complain.

Before you roll out a major health or green marketing campaign, it is worth getting your claims checked. Fixing a problem early is far cheaper – and far less public – than dealing with a regulator and corrective advertising later.

Further Reading

IP Australia – “Copyright basics” (overview of what copyright protects and how long it lasts)

Arts Law Centre of Australia – “Appropriation art and copyright” (practical guidance for artists and photographers)

Mattel Inc v Walking Mountain Productions (Food Chain Barbie)

Ninth Circuit US case on Tom Forsythe’s parody photos of Barbie dolls (fair use found).

https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/appellate-courts/F3/353/792/577041/

Leibovitz v Paramount Pictures Corp (Demi Moore / Naked Gun parody)

US Second Circuit case on the Naked Gun 33⅓ poster parodying Annie Leibovitz’s Demi Moore pregnancy portrait.

http://www.artistrights.info/leibovitz-v-paramount-pictures-corp

https://www.artinfringementdatabase.org/case/leibovitz-v-paramount-pictures-corp

Rogers v Koons (String of Puppies)

US Second Circuit case where Jeff Koons’ “String of Puppies” sculpture was held to infringe Art Rogers’ “Puppies” photograph.

https://www.artinfringementdatabase.org/case/rogers-v-koons

Common “green” claims

- “100% recyclable” – Misleading if parts (labels, caps, mixed materials) can’t be recycled in normal kerbside bins.

- “Carbon neutral” – Risky if you can’t clearly show how emissions were measured, reduced and offset, and for what period.

- “Sustainable” / “eco‑friendly” – Too vague if there’s no specific, verifiable environmental benefit behind the slogan.

- “Biodegradable” plastics – Problematic if products only break down in special conditions, not in ordinary use or landfill.

- “Zero emissions” / “100% green” energy – Can mislead if the claim relies mainly on offsets or averages without explanation

This article explains when using existing photographs or famous images becomes copyright infringement rather than artistic creativity, using real cases (including Barbie and the Demi Moore portrait) to show how courts balance parody, social commentary, market harm and “substantial reproduction”, and how outcomes differ between US fair use and Australia’s narrower exceptions.

Read more here : 35-37 Bus PPMay04.indd

Please note the above article is general in nature and does not constitute legal advice.

Please email us info@iplegal.com.au if you need legal advice about your brand or another legal matter in this area generally.