Used under a Creative Commons Licence

How far can you take creative claims?

Practical guide to puffery, misrepresentation and misleading advertising claims in Australia

This is an updated version of an old post, click here to see the original.

What is puffery?

In advertising and branding, puffery is the legal label for bold, vague, feel‑good claims that no reasonable consumer would take literally.

Think of slogans like “best coffee in the world” or “the ultimate dress for every woman” – they are exaggerated opinions, not precise promises a court can measure.

A classic example is a sports drink claiming “Gatorade always wins”; most people understand this as hype, not a guarantee that every athlete using it will win every event.

Because puffery is so imprecise, it is usually not an “actionable” representation and will not, on its own, amount to misleading or deceptive conduct.

Where the idea of “mere puffery” came from

The famous English case Carlill v Carbolic Smoke Ball Co (1892) is still quoted today when lawyers talk about puffery.

The company advertised that its smoke ball would prevent influenza and promised £100 to anyone who used it as directed and still got sick, even depositing £1,000 at the bank to show it was serious.

Mrs Carlill used the product exactly as instructed and still caught influenza, but the company refused to pay.

The court decided the ad was not mere puffery because the language was specific, and the bank deposit showed a real intention to be bound – it was a serious offer made to the world, not just marketing fluff.

This case teaches two key lessons:

The more precise and serious the wording, the less likely it is puffery.

Offers can be made “to the world” and still be binding if they show clear intention and certainty.

Puffery versus misrepresentation

Misrepresentation (and misleading or deceptive conduct) is very different from puffery.

In simple terms, misrepresentation happens when:

- A statement is untrue at the time it is made.

- It is made to persuade someone to act – for example, to sign a contract, buy a product or lease a property.

- The other person actually relies on that statement when deciding what to do.

An example often discussed in Australia is where a property developer uses sales materials that promise features which do not actually exist in the finished building.

If a brochure says an apartment “includes a lock‑up garage” and a buyer reasonably understands that to mean a secure, individual garage, but instead only gets an open car park with lines on the ground, this is likely to be a misrepresentation, not puffery.

Importantly, misrepresentation is not limited to outright lies.

It can also occur when a business withholds important information, presents only half the story, or uses images and layout to create a false impression.

As Justice White explained in Mitchell v Valherie, puffery covers vague, exaggerated expressions of opinion, not solid statements of fact.

Once you move into specific factual claims – sizes, capacities, results, inclusions, guarantees – you are leaving the safe zone of puffery.

The legal effect of misrepresentation

If a court finds that a statement was a misrepresentation or was misleading or deceptive, several serious consequences can follow.

Depending on the facts, a customer may be able to:

- Rescind (undo) the contract and walk away from the deal.

- Seek compensation for loss suffered because they relied on the misleading statement.

In regulatory cases, see the business face penalties, corrective advertising orders, and enforceable undertakings.

For many creative businesses, the real damage is often reputational: negative reviews, loss of trust and long‑term harm to the brand.

That is why tight control over marketing content – especially fine print, visuals and headline promises – is essential.

The role of Australian Consumer Law

In Australia, these issues sit under the Australian Consumer Law (ACL), in particular:

The general ban on misleading or deceptive conduct in trade or commerce.

Section 29, which prohibits making false or misleading representations, including about:

- The standard, quality, value or grade of goods.

- Whether goods are new.

- Particular benefits, uses or performance characteristics.

- Testimonials or whether someone actually approves or endorses the goods.

So if you say your product is “100% organic cotton” or “clinically proven to reduce wrinkles in 7 days”, you are making factual claims that need to be accurate and properly substantiated.

You cannot hide behind “that was just advertising” once your wording is precise and objectively testable.

By contrast, “feel as fabulous as a supermodel” or “beautiful enough to make you smile every morning” is much more likely to be treated as puffery, because no judge can apply a clear, objective test to those words.

How far can you push creative claims?

The key dividing line is whether a reasonable consumer can give your words a clear, concrete meaning.

Here are some practical guides:

Safe puffery is the kind of loose, subjective language that lives in the realm of opinion rather than hard fact. When a brand talks about being the “best”, “ultimate” or “most loved”, it is inviting a feeling rather than making a precise promise that a court can measure. Similarly, emotional or aspirational phrases like “you’ll feel unstoppable” or “be your own muse” are aimed at mood and self‑image, not at guaranteeing a specific result. Even the big, playful exaggerations – “the last candle you’ll ever need in your life” – are so over the top that most people understand they are not meant literally.

The trouble starts when you move out of this soft, fuzzy zone and begin to anchor your message in concrete details. As soon as numbers appear – percentages, time frames, speeds, savings, volumes – you are no longer just flattering your product; you are making claims that can be tested and challenged. The same is true when you describe ingredients, country of origin, safety, or health benefits: these are matters regulators and courts expect you to get right. Statements about legal rights are even more sensitive. Promises like “lifetime warranty”, “fully insured” or “complies with all regulations” may sound like reassuring copy, but if they are not strictly accurate in the fine print, they can create serious exposure.

Because the dividing line between safe puffery and risky, actionable statements is contextual and often subtle, it is easy for well‑intentioned businesses to drift over it without realising. What feels like creative marketing to a copywriter can look like a misleading representation to a regulator or a court. That is why, once your claims move beyond pure opinion into numbers, benefits, safety, origin or legal rights, it is wise to have a lawyer experienced in advertising and consumer law review the wording and the overall impression before you go live.

Very high risk

Before‑and‑after style promises that suggest guaranteed outcomes.

“Cure”, “prevent”, “reverse” in relation to health or medical‑adjacent products.

Statements that undercut mandatory disclosures or contradict fine print.

As Mark Twain is often quoted, “A lie can travel halfway around the world while the truth is putting on its shoes.”

In the age of screenshots and social media, misleading claims can spread quickly and be very difficult to unwind.

Two famous quotes worth remembering

Advertising law may be technical, but at its heart it is about honesty and clarity.

Two quotes capture the spirit of how to approach creative claims:

- “Advertising is only evil when it advertises evil things.” – David Ogilvy.

This is a reminder that strong, clever advertising is not the problem; it is when it crosses into deception that the law steps in. - “With great power comes great responsibility.” – often attributed in modern culture to Spider‑Man, but relevant to any brand with a platform.

The more influence your brand has, the more carefully you need to handle claims your audience may rely on.

Practical tips for businesses and creatives

If you are crafting creative claims for your brand, consider this checklist:

Ask: could a reasonable customer take this literally and rely on it?

If yes, treat it as a factual representation and make sure you can back it up.

Keep your strongest exaggerations in the realm of mood, feeling and aspiration, not hard outcomes.

Avoid mixing precise facts and puffery in a way that confuses what is a promise and what is mere flourish.

Review visuals, layout and fine print as a whole – the law looks at the overall impression, not just isolated sentences.

As a simple rule of thumb: if a judge could measure it, verify it or disprove it, it is unlikely to be puffery and needs to be true and substantiated.

If it is clearly opinion or over‑the‑top praise with no precise meaning, it is more likely to sit safely in the puffery category.

When to get advice

The line between lawful puffery and unlawful misrepresentation is often subtle and context‑specific.

If you are planning a major campaign, product launch or rebrand with bold claims, it is wise to get tailored legal advice before you go live.

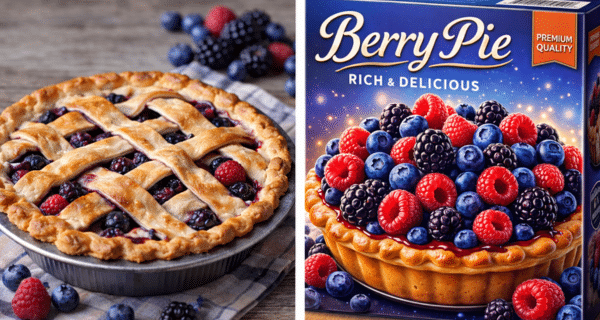

When Labels Go Too Far

- “99% fruit & veg” yoghurt that’s mostly fruit sugar concentrate.

- Baby snacks with fruit pictures but very high total sugars.

- “100% ocean plastic” that’s really coastal‑area plastic.

- Green, leafy packs on ultra‑processed snack foods.

- “Made in Australia” where key ingredients are imported.

- Brown “eco” cardboard around otherwise standard plastic.

- “High protein” cereal that’s low protein until you add milk.

- “Sugar free” drink still loaded with fruit sugars.

- “Keto friendly” snack with high net carbs.

- “Immune support” shots with tiny vitamin doses.

- “Doctor approved” look created just with a lab coat image.

- “Farm fresh” eggs shown on lush hills but from caged hens.

To read more – go here: DIAA-DairyClaims-2010.pdf

Further Reading

How to Avoid Your Brand Becoming Generic

https://sharongivoni.com.au/how-to-avoid-your-brand-becoming-generic/

Protecting What’s Special – Legally Speaking

https://sharongivoni.com.au/protecting-whats-special//

What You Can Do If Someone Copies Your Design

https://sharongivoni.com.au/copycat-products-what-you-can-do-if-someone-copies-your-design/

Protect Your Business Idea and Stop Others from Copying

https://sharongivoni.com.au/first-to-market-heres-how-to-stop-others-from-copying-your-idea/

Small Design, Serious Risk: Favicon Trade Mark Confusion Explained

https://sharongivoni.com.au/small-design-serious-risk-favicon-trade-mark-confusion-explained/

ACCC – False or misleading claims

https://www.accc.gov.au/consumers/advertising-and-promotions/false-or-misleading-claims

ACCC – Advertising and selling guide (includes puffery and examples)

https://www.accc.gov.au/system/files/Advertising%20and%20selling%20guide%20-%20July%202021.pdf

Please note the above article is general in nature and does not constitute legal advice.

Please email us info@iplegal.com.au if you need legal advice about your brand or another legal matter in this area generally.