Used under a Creative Commons Licence

Copyright in Focus – A Photographer’s Legal Win

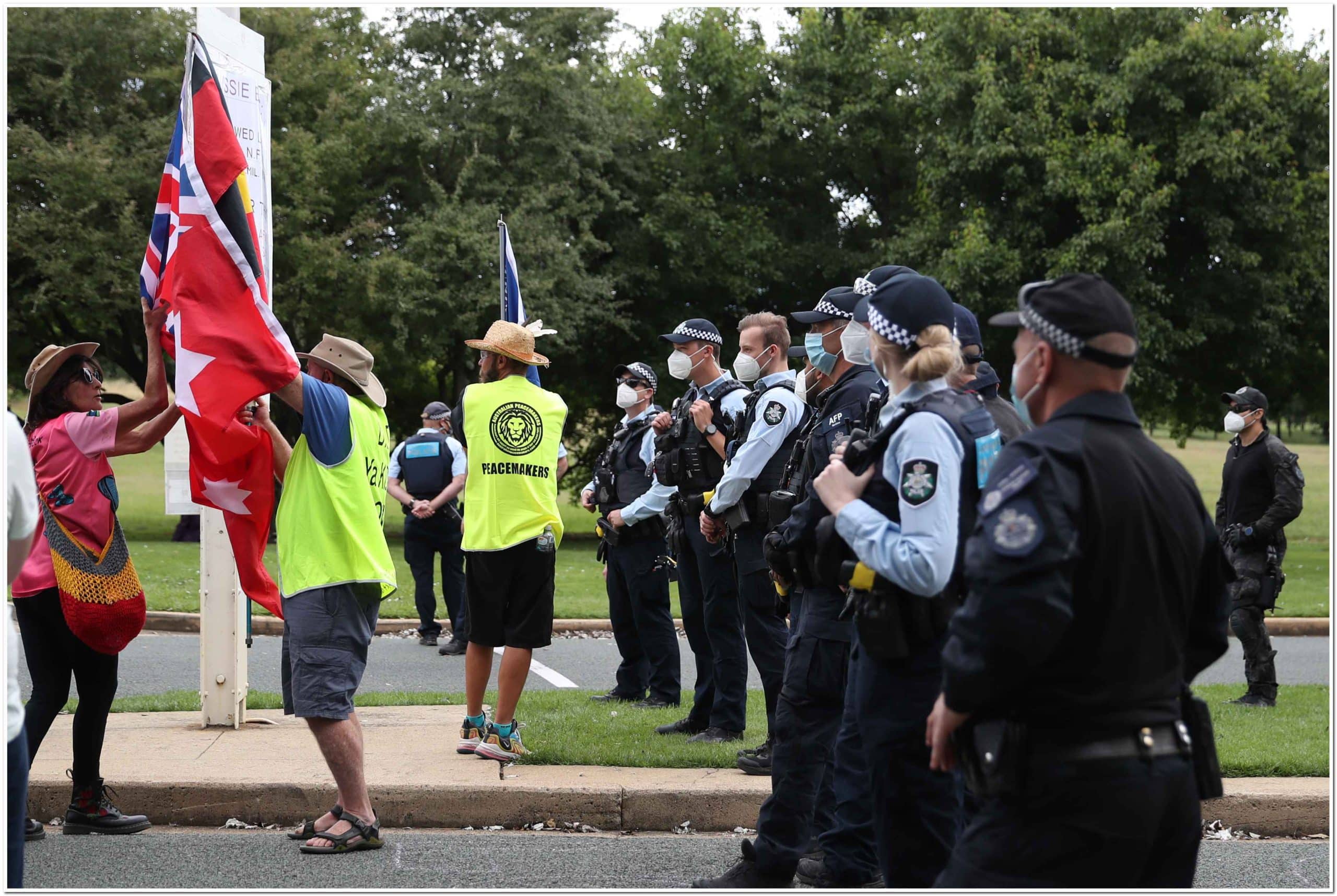

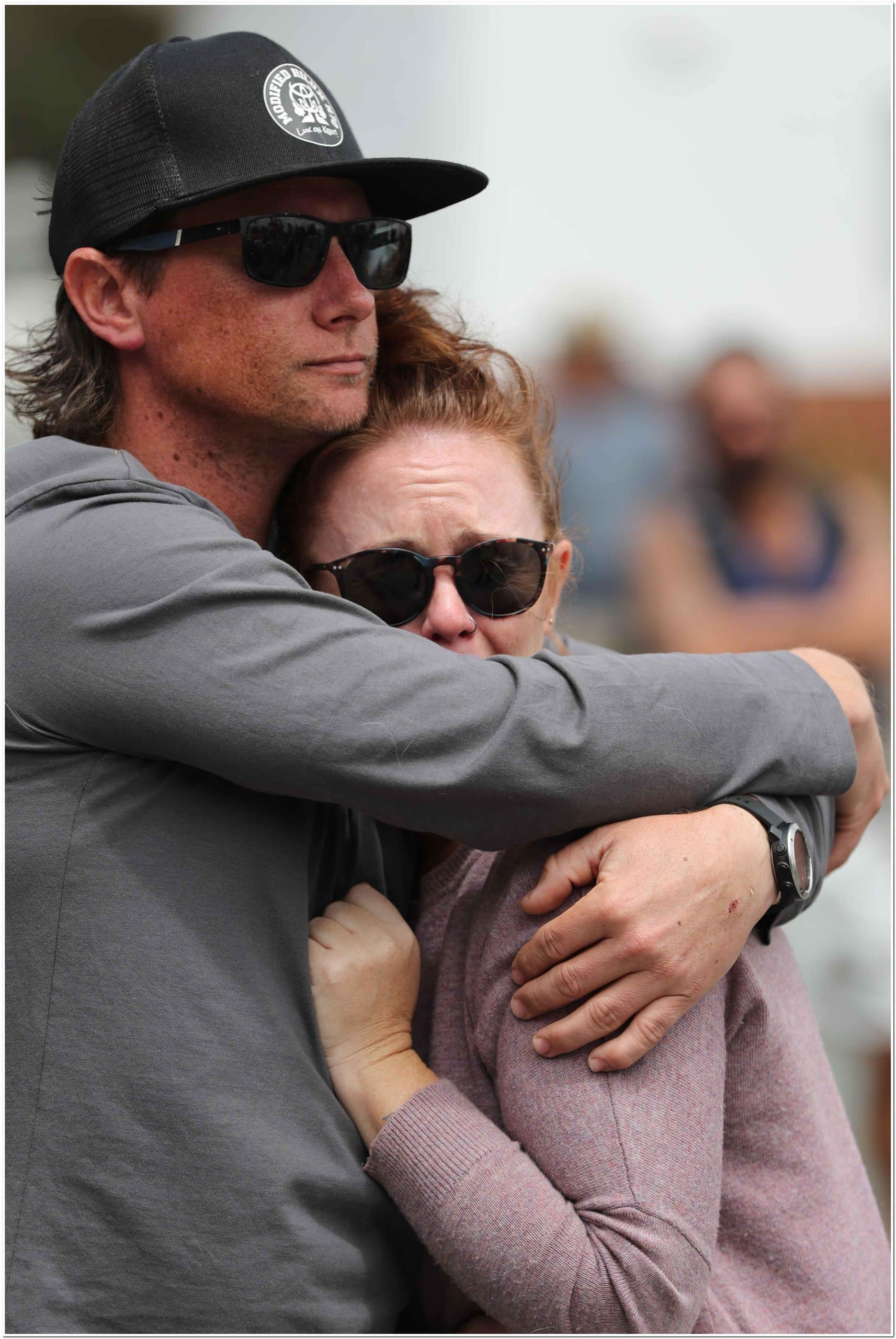

When Gold Coast-based photographer John Napper took compelling portraits during the Convoy to Canberra protests in 2022, he probably didn’t imagine that his images would one day become the subject of a court decision.

But that’s exactly what happened—and the legal lessons that followed are significant for creative professionals.

The matter of Napper v The Publisher [2025] is a reminder that copyright and consent are more than industry buzzwords—they’re enforceable rights under Australian law.

By way of background, John Napper is known for his striking photojournalism, particularly his coverage of political demonstrations, civil unrest, and social movements and his work has been published in independent media.

In 2023, a journalist and publisher released a book that incorporated several of Napper’s protest images. But those images had never been licensed. Worse still, Napper wasn’t properly credited, and the photos were altered and placed among other contributors’ work—without his permission.

After discovering the book, Napper instructed Sharon Givoni Consulting to act on his behalf. Proceedings were commenced in the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia. Judgment was delivered in May 2025.

The court found there was no clear licence permitting the publisher to use or modify the photographs. It also found that Napper’s moral rights had been violated: his name had been either omitted or misspelt, and the publisher’s conduct was compounded by the continued use of the photographs even after the dispute was raised. The judge was not persuaded by the publisher’s evidence, describing it as evasive and inconsistent, which weakened his position.

The Court awarded Napper $192.02 in profit share, based on the publisher’s book sales and the proportion of that profit attributable to Napper’s work. In addition, the Court ordered $12,000 in additional damages under section 115(4) of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth).

These damages are designed to punish serious or flagrant breaches of copyright—not just compensate for losses. An injunction (a legal order prohibiting further unauthorised use) was granted, and the publisher was also ordered to contribute to Napper’s legal costs.

The decision sent a clear message: photographers have enforceable rights, and using their work without permission carries consequences.

This case reinforces several key principles:

- Copyright in photographs is automatic—no registration required.

- Attribution is not optional. Photographers have a right to be credited.

- Permission to use a photo must be express and clearly agreed.

Zooming In on What Happened

John Napper, a Queensland-based photographer recognised for his emotionally charged protest imagery, was part of a creative collaboration that quickly turned into something else. In early 2022, Napper documented the Convoy to Canberra protests—one of the most significant grassroots demonstrations in recent Australian history.

The intention was to produce a book combining Napper’s photographs with a written narrative by a journalist. However, things went off track. Without Napper’s permission, the publisher included the images in a commercially available book, presented alongside other content, and made available on Amazon.

While Napper was credited in some places, his name was misspelt, and in other instances, it was left off altogether. That’s not just sloppy—it’s a breach of the photographer’s legal rights.

Upon discovering the unauthorised use, Napper reached out to our firm for assistance.

And rightly so. Copyright law is clear: the creator of an image owns the rights to it. Unless there’s a licence (in other words, express permission) granting someone else the right to reproduce or publish it, that use is unlawful.

The Law in Focus: Copyright and Moral Rights

In Australia, copyright in photographs arises automatically the moment the image is created. The photographer doesn’t need to register it, stamp it, or pay a fee.

Copyright gives the creator exclusive rights to use the work, and any use by others must be authorised.

Equally important are moral rights. These protect the photographer’s personal connection to their work. Moral rights include the right to be properly attributed, the right not to be falsely attributed, and the right not to have your work altered in a way that harms your reputation.

They’re not optional. They’re enshrined in law—and they continue to exist even after copyright is licensed, unless the creator explicitly waives them in writing.

In this case, Napper wasn’t just overlooked—his work was used without approval, and his name was used inconsistently in the book so there were attribution issues.

The Bigger Picture

This case isn’t about “artistic disagreements” or creative license.

It’s about a photographer’s right to control their work, receive credit for it, and be respected as a professional. The Court recognised this and awarded not only the small sum of profits Napper was entitled to, but additional damages that sent a very clear message.

Photographers, whether amateur or professional, must take steps to protect their work.

Use written agreements. Clarify usage terms. If someone asks for your files, don’t assume that means they understand copyright law.

And always keep documentation. Even informal communications—emails, DMs, text messages—can help build a picture of what was agreed (or not agreed). These records become crucial if a matter escalates.

About John Napper

John Napper is a Queensland-based photographer and the founder of Action in Focus Photography.

Photograph: John Napper

Photograph: John Napper

Photograph: John Napper

Photograph: John Napper

Please note the above article is general in nature and does not constitute legal advice.

Please email us info@iplegal.com.au if you need legal advice about your brand or another legal matter in this area generally.